Though there are many forms of the evil eye, the most common one in Brazil often isn't intentionally malicious; in fact, the danger comes from admiration. If someone compliments my clothes or appearance or anything else, it shows the possibility of envy, and that envy has consequences; in fact, in Portuguese, the word "evil" doesn't enter into the dynamic. People fear the "olho gordo" or fat eye, the desire of the other for what I have. It makes sense in a culture that has long been poor, and where social equality (within an economic class, though not from one to another) is an important virtue.

The problem comes when the object of envy is a baby. If someone else admires Helena Iara, or envies Rita and me because she is our daughter, that envy can make her sick. An entire social group of "benzedeiras" or blessers (sort of like good witches) exist in order to help kids get over the illnesses caused by the evil eye. This struck me as sort of silly... until Helena became the victim of the olho gordo, as she did last week, with fever, confusion, and inability to sleep.

Lest you think I'm getting soft in the head, let me explain what I think happened. In Recife, blond children are uncommon, and because they are almost always the children of the rich, they seldom turn up in the favelas and areas of urban decay where we spent most of our time. For that reason, Helena attracted a lot of attention. A lot. She literally stopped traffic from time to time, and people surrounded her as if she were a rock or soap opera star, each one of them with more extravagant compliments. In a city of almost 3 million people, one of the dirtiest and hottest and noisiest places I know, it was just too much. Helena became over-stimulated and got sick.

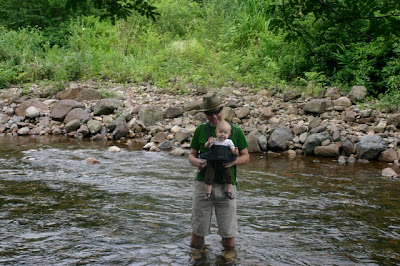

A benzedeira blessed Helena, and I doubt that it did any harm -- in fact, the kind and soothing words of the woman, and the sweet-smelling fond she swung around Helena probably helped. But what really worked was rest: getting her away from the chaos of the city, from the intense and desiring eyes of thousands of people. She still had to deal with the heat, but she soon was as happy and healty as she had ever been. And I came to have a little more respect for folk beliefs that I used to think were all confused with magic...